From ambition to implementation: delivering the energy transition and industrial transformation in 2026

Insight by Sandra Ghosh, Susanne Lein

Insight by Morton Hemkhaus

The market for electronic devices is growing rapidly worldwide, and has a become problem. Mobile phones, tablets, laptops, and white goods like refrigerators and freezers have ever-shorter innovation cycles. Their short life leads to a growing mountain of electronic waste (e-waste).

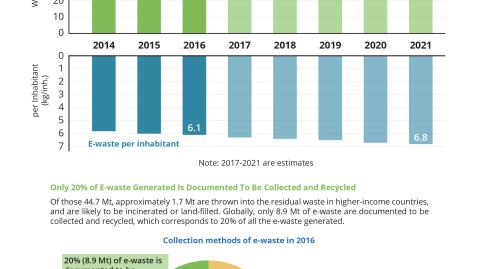

According to a study by the United Nations, we produce 50 million tons of electronic waste per year. That amount of waste weighs more than the combined weight of all aircraft ever produced, the study notes. The authors warn that the amount will rise to 120 million tons by 2050.

These devices are rarely disposed of properly around the world – most are burned, buried or taken apart under precarious conditions. This practice not only endangers the environment and the health of thousands of people in countries such as China, Ghana and India, it also destroys over 50 billion euros worth of material.

In an interview, Morton Hemkhaus (adelphi) explains why the problem is growing and what forms of support the affected countries need.

Electronic waste is not a new problem, and we do a lot to combat it. Why is it still in the headlines so often?

Morton Hemkhaus: Thanks to the increasing digitisation, electronic waste remains a hot issue. Modern information technologies are spreading more and more as we all take advantage of their potential for the future – in both developed and developing countries. This creates a growing mountain of consumed units, which in turn fuels the problems associated with their disposal. This is the dark side of digitisation, which has been made visible by worldwide digital networking and a common topic in the media.

What are the reasons for this?

Morton Hemkhaus: The media often presents an image of Africa that is suffering from the waste products of civilisation that we in industrialised nations do not want to dispose of ourselves. However, numerous studies and projects show that, thanks to the Basel Convention, the export of hazardous waste, including electronic waste, has declined sharply. The majority of exports are used electronics that are sold as second-hand goods in the Global South.

I see two major trends: increasing prosperity and ongoing digitalisation in emerging and developing countries. Both trends lead to rising demand for used electrical appliances. These can be imported legally, but after a relatively short life they end up in the trash. There is a lack of proper collection, processing and disposal for electronic waste – which means the problem is growing quickly.

What cause the problems in those countries?

Morton Hemkhaus: The disposal is often disorganised and left to the so-called ‘informal sector’. This term refers to people who make a living from elecrontic waste materials without official approval. They go from house to house and collect scrap metal, which they use or sell to informal recyclers.

In both cases, things like electrical cables are burned in backyards in the open air in order to extract the copper – without any protection for human health or the environment. But these informal recyclers are more competitive than authorized companies that comply with environmental and social standards, among other cost structures. This is an economic dilemma and makes it difficult to find solutions on site.

Where do you see effective solutions?

Morton Hemkhaus: Given the enormous material flows that are coming our way, we need to better understand how much electronic waste there actually is. The Global E-waste Monitor of the United Nations University provides reliable statistics on future growth rates as well as registered and non-registered disposal.

On the international level, iniatives like this prove successful when they rely mainly on voluntary standards and engagement for avoiding electronic waste. One example is the Initiative ‘Solving the E-Waste Problem’ (StEP), which adelphi is a part of. We recently joined the PREVENT Waste Alliance as part of the working group looking for innovative solutions to recycle old electrical appliances.

What can the affected countries do?

Morton Hemkhaus: On the national level, the establishment of systems of extended producer responsibility is key. The distributors – that includes both producers and importers – have to be held accountable for the disposal of electronic waste, which can mobilise huge financial resources for the development of waste management. In addition, we must recognise that it is impossible to prohibit the informal sector. People collect enormous amounts of electronic waste – this is an effective survival strategy for many of them.

How can we maintain the informal nature of their work, but protect them better and incorporate them into formal structures? That is crucial question, in my opinion, and adelphi, for example, is writing guidelines for Ghana, developing practical information, offering training sessions and evaluating existing programs. Moreover, tools like the Business Plan Calculator help companies in the StEP initiative establish larger and safer dismantling units.