From ambition to implementation: delivering the energy transition and industrial transformation in 2026

Insight by Sandra Ghosh, Susanne Lein

Insight by Christopher Kardish

The Covid-19 pandemic has left its mark on the year 2020. Its effects on global CO2 emissions have been widely discussed. But how have emissions trading systems fared, both existing and in development? The yearly status report by the International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) takes a detailed look.

Over the past year, emissions trading systems (ETSs) have seen it all: expansions to new places, steep price declines, rapid price increases, reforms, and new beginnings – all amid a pandemic that has upended our way of life and left no sector or country unaffected.

The Emissions Trading Worldwide Status Report 2021, published annually by the International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP), aims to deliver a comprehensive view of these developments as well as what’s happening in ETSs that are already in force and those still to come online. What follows is a global stocktake and a sense of how carbon markets have responded to the pandemic.

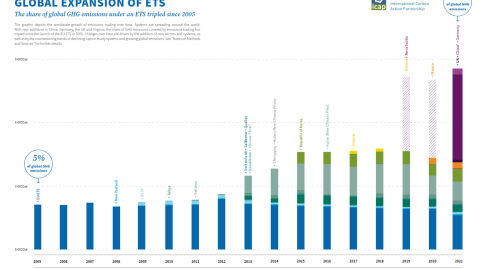

Undoubtedly China takes the spotlight this year with the announced launch of its national ETS. Covering about 4 billion tonnes of CO2, or 40 percent of national emissions, the system is now the largest in the world and nearly doubles ETS coverage to about 16 percent of global emissions (see the figure below), according to the 2021 ICAP Status Report.

However, the China national ETS starts slow, with only the electricity sector, limited obligations for emitters, and no hard cap. Emission allowances will be distributed for free using benchmarks. Additional costs for coal-fired plants will be limited to 20 percent of their emissions that exceed the benchmark, while natural-gas facilities face no obligations beyond their free allowances. The cap is intensity-based rather than setting an absolute limit on total emissions and calculated from the bottom up. Still, the launch marks a milestone in Chinese climate policy, with future expansions and reforms anticipated to help achieve the country’s 2060 target of carbon neutrality.

The German National ETS represents an expansion to new sectors. It applies to transport and heating fuels, which are not currently covered by the EU ETS, though debate at the European level about an expansion continues as the EU considers reforms aimed at delivering a higher 2030 target.

This year also marks the start of the UK ETS following Brexit. Its cap begins five percent below where it would have stood under the EU ETS, with plans in place to align the cap trajectory with the UK’s net-zero target. By 2030, the UK aims to be 68 percent below 1990 emissions. While the UK ETS resembles the EU ETS to start, policymakers are considering a number of future changes, including sectoral expansion, rules on free allocation, and how to incentivise GHG removals.

Lastly, the ranks of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) grew as Virginia joined the collective of 11 Northeast and mid-Atlantic states. Other states that may join in the years ahead include Pennsylvania, which would expand the size of the market by nearly 75 percent.

All told, 24 systems are now in force across the globe.

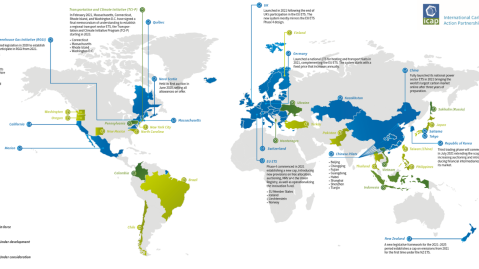

Another 22 governments are considering or actively developing an ETS. Asia in particular is a region to watch and shows a spectrum of development (see the figure below). South Korea became the first in the region in 2015 and is entering a new stage of its development (Phase 3) with a tighter cap and greater use of auctioning and benchmarking.

Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand are all at various stages of pilot testing, developing market infrastructure like emissions monitoring, and laying the legal and regulatory groundwork to launch compliance systems in the years ahead. Japan’s net-zero pledge and instructions from Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga to consider carbon pricing are promising developments for climate policy. Meanwhile, other countries are considering legal mandates for emissions trading, including the Philippines.

In the Americas, a number of individual US states, including Oregon and Washington, are considering ETSs, while the multi-state Transportation and Climate Initiative Program – aimed exclusively at the transport sector – is expected to launch in 2023. In Latin America, Colombia is completing technical work to launch a pilot system in 2023 or 2024, and Mexico is continuing its pilot system, with a timeline for the mandatory phase to begin operation in 2023.

In Europe, Ukraine continues building ETS infrastructure by collecting data, and recent statements from the minister of environment signal an ETS could launch as early as 2025. Russia, meanwhile, is developing a pilot system in the Sakhalin region as a testing ground for GHG regulation in other regions.

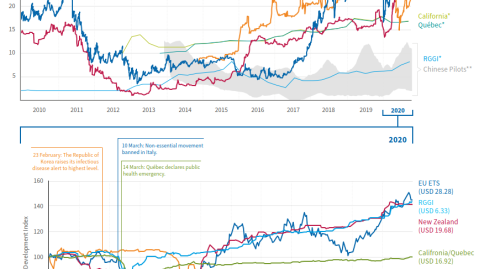

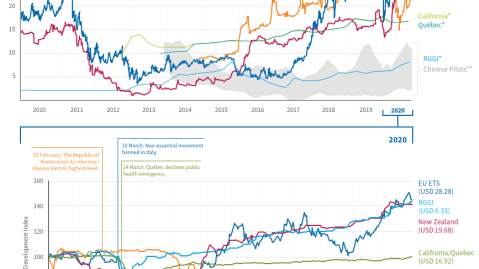

As COVID-19 led to lockdowns and steep declines in economic activity across the world, allowance prices in long-standing ETSs tumbled too. This raised questions about how far prices would fall and for how long they’d slump, given the scale of pandemic-induced recession and memories of the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, which contributed to a protracted period of low allowance prices in the EU ETS and tested confidence in the ability of carbon markets to do the heavy lifting in the green transition.

Other external factors beyond economic downturns have always played a role in low carbon prices in the EU and elsewhere, including wider developments in energy markets and overlapping government policies on climate. But COVID-19 has presented an unforeseen shock with strong potential to destabilize carbon markets. So far, that has not come to pass.

The pandemic’s impacts on emissions regulated under the world’s carbon markets remains to be seen, as inventories tracking this data typically lag. However, there are clear signs that COVID-19 will not stymie the effectiveness of ETSs to provide a price signal and incentivize abatement. Critically, by June of 2020 allowance prices in most markets had begun to rebound (see the figure below). Allowances prices closed the year 45 percent higher in the EU, 41 percent higher in New Zealand, and 43 percent higher in RGGI, while in North America’s linked Western Climate Initiative market of California and Québec prices returned to pre-pandemic levels.

This resilience is likely due in part to two factors. First, ETSs have established rule-based mechanisms to control the price or quantity of allowances for more predictable market conditions, and these mechanisms are more widely in place than in 2008. The EU’s Market Stability Reserve, for instance, controls the overall supply of allowances based on certain measures of total allowance volumes and took effect in 2019. In California, there is a minimum price at auctions that increases each year and protects against a price crash. By the end of 2020, California’s auctions were selling out again and prices in the secondary market converged with those in government auctions. In RGGI, prices quickly settled above a key trigger point that came online in 2021 that restricts supply when the price trigger point is reached.

A second factor is likely the impact of future market expectations as governments pursue more ambitious 2030 targets and net-zero commitments, along with reforms aimed at meeting those goals. This is likely true of the EU and New Zealand, among others. Sweeping reforms to the New Zealand ETS took effect this year, including the end of a fixed-price option that acted as a price ceiling, while the EU is raising its 2030 target from 40 percent below 1990 levels to at least 55 percent, signalling a tightening supply of allowances.