From ambition to implementation: delivering the energy transition and industrial transformation in 2026

Insight by Sandra Ghosh, Susanne Lein

Insight by William Acworth

Pricing carbon ensures that the costs associated with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are embedded in production and consumption choices. In Europe, a broad price on carbon has been established since 2005 through the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) as well as supplementary sector-specific carbon taxes/ETSs in some Member States. The future of carbon pricing in Europe is at the heart of the EUGD, which addresses the design of the EU ETS; the imposition of carbon pricing on imports to protect against carbon leakage and a loss of competitiveness; the role for and type of carbon price to be applied to the transport, building, and maritime sectors; and how the impacts of this transformational change can be distributed fairly among Europeans across the board. The key components of the EUGD interact with one another, and policy choices cannot be taken in isolation, which adds another layer of complexity to policy discussions and technical debates. Here, we create an overview of the various carbon pricing elements of the EUGD – what is occupying the current debate, what lies ahead, and how these fit into broader EU and international climate policy on the road to a resilient, net-zero future.

The European Green Deal touches upon virtually all policy areas in the EU. Carbon pricing is connected to many of these. Source: European Commission

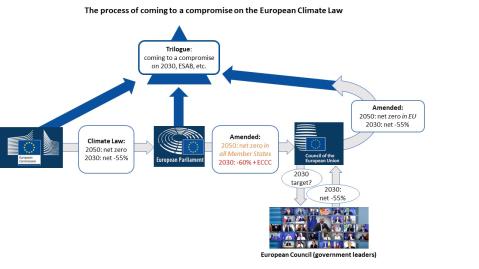

The most monumental achievement of the EUGD in 2021 is the (as yet provisional) adoption of the European Climate Law, which will enshrine into legislation the bloc’s goal for climate neutrality by 2050, as well as an intermediate GHG reduction target for 2030. The European Commission proposed the law in September of 2020 with a 2030 reduction target of 55% compared to 1990 levels. A month later, however, the European Parliament voted to amend the law, increasing the 2030 target to 60%. In December, following a debate that went on throughout the night, European Member States agreed to support the Commission’s 2030 target of at least 55%. The discussion moved into a trilogue—a series of negotiations between the Council, the Parliament, and the European Commission—to settle on a shared version of the legislative text. Despite the determination of Parliament representatives, especially those from progressive parties, to increase ambition, an overnight negotiation session ending early morning on April 21 eventually led to a compromise on 55%.

Although the headline figure of 55% did not change, the Parliament did not leave the negotiation table empty handed. Firstly, the original target as proposed by the Commission and supported by the Council was a net 55% reduction by 2030. A net target implies that carbon sinks and removals count towards the goal and that the expected needed reduction to achieve the target would only be 52.8%. The Parliament, on the other hand, argued in favor of an absolute reduction target, excluding sinks. In the compromise deal, the use of sinks is limited, so that the needed reduction by 2030 effectively increased compared to the Commission’s proposal. Secondly, the deal contains a commitment to tie an interim 2040 reduction target to carbon budget calculations, to be determined in 2023. This budget will indicate how much can still be emitted until 2050 without violating the Paris Agreement. With these two tweaks, the Commission will have to increase its climate efforts, albeit not as drastically as had a 60% reduction target been decided.

A third win for the Parliament is the establishment of an independent scientific advisory panel on climate change, the European Scientific Advisory Board. The board will advise on existing and proposed climate policies and their alignment with GHG targets. In the future, it could take on a role similar to that of the Climate Change Committee in the UK or the Climate Change Commission in New Zealand, which make recommendations on emissions budgets that can in turn be reflected in the caps of the countries’ respective ETS.

To reach this the newly decided 2030 emissions reduction target, the European Commission will publish a suite of policies by June 2021, known as the ‘Fit for 55’ package. Alongside policies for renewable energy, energy efficiency, tax reforms, and performance standards, this package will include major reforms of the EU ETS. The following sections delve first into discussions surrounding a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), followed by what can be expected in the reform of the Market Stability Reserve, and the possible expansion of the ETS to additional sectors.

A highly anticipated ETS policy development is the EU’s proposal for a CBAM. EU ETS allowance prices recently broke 44 euros and although the increased allowance prices send a stronger mitigation signal, they also raise concerns about international competitiveness and carbon leakage for the covered sectors. Until now, the EU has addressed competitiveness concerns by handing out free allowances to emissions-intensive and trade-exposed industries included on a carbon leakage list. But as the system matures, free allocation is slowly being phased out. From 2021, the benchmarks used for free allocation have been updated and will decline annually.

The CBAM is a policy intended to ensure that an effective carbon price signal in all EU ETS sectors can be retained in a world where climate policies across borders are not equally stringent, thereby addressing competitiveness and leakage risks. For some sectors covered by the ETS within the EU, a CBAM would aim to impose a similar carbon price on imports. This would alleviate concerns about European installations having to pay a price for their emissions when their foreign competitors do not. The European Commission held a public consultation on the topic and will publish an impact assessment alongside its proposal for the CBAM’s design by June 2021. The CBAM could take several forms, each with their own risks and opportunities, and would raise complex design issues in different sectors, as described in detail in a sectoral analysis of CBAM by the European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition (ERCST).

In terms of overarching design, the most straightforward option would be to impose a customs duty on products based on their carbon content, effectively a “carbon tariff”. Other options on the table are a consumption charge or a notional ETS. The latter currently seems the most favored option, highlighted by recent statements from the bloc’s Trade Commissioner, as well as by the European Parliament, which took the initiative to establish its own position. A notional ETS would entail the creation of a separate system, exclusively for firms exporting to the EU. Producers would need to buy allowances for their emissions at a price likely pegged to the EUAs, but these allowances would not be tradable. The Parliament has also expressed the need to expand the system over time, but to begin with implementation on imports in the power and energy-intensive industrial sectors. Likely candidates for an early CBAM are the cement, steel, electricity, and chemical sectors.

Whether the CBAM takes the shape of an explicit carbon tariff or not, it could lead to free trade concerns with the World Trade Organization (WTO). These are not insurmountable and depend heavily on the design of the mechanism, but it will be a challenge to design it in a way that mirrors the costs of domestic producers and creates a level playing field. The WTO’s most-favored-nation rule forbids differentiated treatment of the same import product. This decreases the possibility of tying the CBAM price to benchmarks based on the average emissions intensity per country, a potential way to better reflect their true carbon content. Even if such an approach were possible from a legal perspective, it faces data and administrative challenges. Tying the CBAM to the price of allowances under the EU ETS and using equal benchmarks across the board will be a step in the right direction, but this may provide overly generous assumptions in many cases, and there are many other choices that could prove detrimental to the design of a WTO-compliant mechanism.

Another potential hurdle is the allocation of free allowances. The initial version of the Parliament’s own initiative, as drafted in the Environment Committee, proposed that the CBAM would lead to “the gradual phasing-out of the free allocation of allowances until they are completely eliminated.” But when the initiative was adopted by the full Parliament, it was amended to remove the clause on phasing out free allocation, as a compromise with business interests. Proponents of this approach argue that only costs above the free allocation benchmark would then be charged at the border. But the tenability of this approach is questionable. Upholding free allowance allocation for domestic producers while charging importers from the same sector for their emissions significantly increases the risks of violating WTO rules, even if a sound methodology is found to avoid “double protection” domestically.

The issue of free allowances is particularly important to European exporters. Although a CBAM import measure may help level the playing field within the European market, it does not solve the problem for European exporters. When exports produced under the EU ETS compete in markets abroad where other producers do not pay an emissions price, European exporters could still be at risk of carbon leakage. Continued free allocation could protect European exporters, as could the proposed alternative of compensating European exporters through rebates – essentially the inverse of the import measure. Both of these options, however, may be perceived as an implicit subsidy on exports and again raise WTO concerns.

A final design consideration is the revenue that a CBAM would bring in and how it will be used. Although additional revenue is always welcomed, especially in times of economic crisis, European Commission members have been careful to frame the CBAM as a climate or level playing field policy, rather than a money-making scheme. To ensure credibility, revenue should be spent on climate policy, either in Europe or abroad. Some experts have suggested using the revenue to help developing countries advance their decarbonization efforts, capacity to monitor and report emissions, and establish a carbon price of a similar level.

As significant as the changes may be for the EU ETS, the biggest impact of the upcoming CBAM will be felt beyond the European continent. The advent of this measure has already raised concerns with some of Europe’s main trade partners. Recently, ministers from China, India, South Africa, and Brazil issued a joint statement, expressing “grave concern” about a unilateral carbon border adjustment and stating that it would go against the Paris Agreement’s principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. A CBAM is meant to level the playing field, but that means levelling the playing field upwards. The mechanism will inevitably have some sort of exemption or reduction for imports that already face a price for their emissions at home. Effectively, this means that exporters to the EU will have to step up their climate ambition, or else pay. Who exactly will be eligible for exemptions or reductions remains an open question and will be an enormous methodological challenge, especially if the EU looks beyond carbon pricing and assesses other climate policies in place among its trading partners.

Still, some major EU trading partners are not waiting in the wings. Already in the first months of this year, the Russian government unexpectedly launched an ETS pilot in the province of Sakhalin, and the Ukrainian government announced it would launch its national ETS by 2025. An expert survey in the Asia Pacific region by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung found that industry is often ahead of governments, seeing an EU CBAM as an inevitable driver towards decarbonization measures. The threat of a carbon tariff is forcing Europe’s trade partners to consider the cost of their (lack of) climate policies. Some other countries, including the UK, Canada, and the US, have even shown an interest in developing a border carbon adjustment of their own. By rewriting the rules of the ETS at home, the EU is cementing the CBAM as a key policy to follow – for everyone.

In place since 2019, the Market Stability Reserve (MSR) of the EU ETS is an automatic adjustment mechanism designed to tackle the surplus of allowances accrued in the system in Phases II and III and to maintain a supply-demand balance of allowances by altering auction volumes. While not directly targeting prices, the MSR does affect expectations surrounding the future scarcity of allowances and therefore allowance prices. This allows the EU ETS to provide a more stable and predictable carbon price signal, which is necessary for long-term decarbonization and increasing the market’s resilience to unexpected exogenous shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

As emissions trading in the EU matures, the MSR is subject to periodic review to ensure it is equipped to absorb future external shocks. As part of the structural reforms envisaged for the EU ETS as it enters Phase IV (2021-2030), the first MSR review is scheduled for June of this year, with subsequent reviews every five years thereafter.

Currently, the rule-based MSR is triggered and adjustments to annual auction volumes made if the total number of allowances in circulation (TNAC) rises above 833 million or falls below 400 million. If the upper threshold is reached, the future allowance auction volume is reduced by an amount equal to the withdrawal rate x the TNAC. The Reserve’s current annual withdrawal rate of 24 percent is set to halve in 2024 to 12 percent. If the TNAC falls below the lower threshold, 100 million allowances are released from the MSR to the auction volume. The number of allowances held in the MSR post-2023 will also be limited to the auction volume of the previous year, with any allowances above this threshold permanently invalidated.

Three issues will be central to the MSR review. First, the setting of the allowance thresholds. The current thresholds, which have remained unchanged thus far, were set in line with what has been coined the “hedging corridor”, or the number of allowances considered necessary for participants to hedge their allowance price risk when they sell products on forward contracts, mostly in the electricity sector. Discussions center on whether the thresholds are indeed set correctly or whether they need to change to reflect changes in hedging behavior as well as the declining cap.

Secondly, the invalidation of allowances held in the MSR. The surplus of allowances emerged largely due to the economic crisis of 2007-2008 and high imports of international credits. This surplus is almost universally deemed to be excessive and should not be allowed to continue to undermine the system in the years to come. By many, invalidation was considered necessary to ensure that the MSR provided sufficient foresight surrounding future scarcity of allowances, taking into account not just exogenous shocks but also scenarios with steep (potentially unexpected) decreases in emissions and therefore also a long-term, structural surplus. However, some have argued that this is an indirect way of adjusting the allowance cap, which could create mistrust in the policy instrument, especially as this should be the role of the Linear Reduction Factor. If the invalidation clause is to stay, there is discussion as to whether pegging the size of the Reserve to the preceding year’s auction volume is the correct approach. As auction volumes decline, the MSR’s ability to respond to future scarcity by releasing allowances to the market will be jeopardized in the medium to long run. This debate is far from over and will continue to be a key fight within MSR reform debates.

Third is the design of the injection and withdrawal rates. There has been much discussion as to whether to preserve the current withdrawal rate or go through with the default decrease back to 12 percent, with countries such as Denmark and Italy arguing to keep it at 24 percent to ensure maximum protection against future allowance surpluses. Modeling has shown that even the 24 percent withdrawal rate could be insufficient to reduce the surplus that has already accumulated in the market or cope with the impacts of the pandemic. To combat this, a withdrawal rate that is proportional to the size of the surplus may be an alternative design solution.

Finally, others question the underlying logic of such a quantity-based mechanism. These claim that the mechanism should rather be triggered by the price of allowances, as price is arguably a better indicator of changes in scarcity, and as the current TNAC-based rules may make the ETS susceptible to gaming. A price-based mechanism could also speed up the MSR response but would entail a much more complex overhaul of its architecture. Whatever the result come June, the review of the MSR’s key design features is expected to form a major part of the Fit for 55 proposal.

Expanding the scope of the EU ETS to include road transport and buildings via an amendment of the EU ETS Directive is also very much in the current policy debate, due to the sectors’ high emissions from fuel combustion. These two sectors are currently regulated by the Effort-Sharing Regulation, which sets binding annual national emission reduction targets. Expanding ETS coverage to include them would entail moving a significant part of non-ETS emissions from the ESR’s remit into the EU’s carbon market.

Perhaps central to the debate is whether carbon pricing can reach a level where it can be effective in inducing the necessary change, while maintaining its social acceptance. The high inelasticity of demand for vehicular travel and heating/cooling across Europe also requires the availability of alternatives such as good public transport infrastructure or access to and support for energy efficiency and other measures. It is therefore often argued that coverage under the EU ETS would increase the mitigation burden on the power and industrial sectors, while achieving little in terms of transforming the transport and buildings sectors.

In addition, there is the technical question surrounding the point of emissions coverage. Transport and buildings are particularly challenging, due to the presence of many thousands of individual (and, in the case of road transport, mobile) emission sources which makes the downstream approach of the EU ETS practically impossible for these sectors. While solutions of “mixed coverage” have been found in jurisdictions such as California and New Zealand that operate ETSs with broad coverage, the administrative feasibility of such an approach across European Member States, which have their own administrative and legal structures, is yet to be tested.

In response to the above challenges, proposals are emerging for a separate ETS for the transport and buildings sectors, akin to Germany’s fuels ETS, which could in the future be linked to the EU ETS. Conventional wisdom is that a single, economy-wide carbon price is the most efficient approach to reducing emissions. Over the longer term, this is not disputed. But for the short term this idea has come under scrutiny, with the recognition that there are sector-specific barriers that make some sectors more “allowance market ready” than others. The suggested remedy is then to allow differentiated carbon prices in the short term and to take the time to reduce the sector-specific barriers to carbon pricing. One example here is investment in low-carbon public transit systems that can provide a viable alternative for commuters compared to having to bear the burden of higher fuel costs.

Social acceptance of increased gasoline and fuel prices are also a political risk, as seen in the 2018 Gilet Jaunes movement when the burden of increased fuel prices as a result of tax hikes fell disproportionately on the working and middle classes. In any case, public consultation on the matter took place between November 2020 and February 2021, with key themes including the contribution of the EU ETS to overall 2030 climate ambition, the use of revenues, and low-carbon support mechanisms. Talks continue.

Shipping makes up 90 percent of international trade and 2.5 percent of global annual GHG emissions. Unchecked, maritime transport emissions could increase between 50 and 250 percent by mid-century, completely undermining the goals of the Paris Agreement. Against this backdrop, the United Nations International Maritime Organizations (IMO) has been working to deliver a global agreement for the sector. The EU in principle supports this effort.

However, IMO progress is often blocked by large flag states and is seen by many to be slow. A 2018 amendment of the EU ETS Directive laid out the need to take urgent action in the sector. Despite resistance from various groups concerned about loss of EU competitiveness and the risk that the move could derail international decarbonization progress, the process of expanding the scope of the EU ETS to include maritime transport is high on the EU’s policy agenda. In line with the EUGD, the European Parliament voted in September 2020 to include ships with an overall internal volume of over 5,000 gross tonnage (representing 90 percent of total maritime emissions) in the EU ETS as early as 2022, through an amendment to the existing EU Monitoring Reporting and Verification (MRV) Regulation. The European Commission’s proposal to reform the ETS to include maritime as well as a dedicated impact assessment are expected in June 2021. Pending approval by EU lawmakers and Member States, it will be implemented by 2023. If included, intra-EU shipping would expand the scope of the EU’s carbon market by three percent. If extra-EU voyages are also included, this number could rise to up to nine percent, but observers fear international diplomatic tensions similar to when the EU attempted (and failed) in 2012 to expand the EU ETS scope to cover all aviation to and from European Economic Area (EEA) airports.

Many foundations for the inclusion of maritime transport into the EU ETS are already laid. MRV obligations for CO2 emissions from large passenger and cargo ships docking at ports in the EEA have been in force since 2018. The IMO has since also introduced a global MRV requirement; ships in the EEA are now under double reporting duty. The European Commission’s September 2020 impact assessment included “at least intra-EU” maritime in ETS in all its non-baseline policy scenarios. Powerful European shipping firms and associations, who although would prefer a carbon levy or a move to alternative fuels, have reacted positively to EUGD’s climate ambitions as a whole and acknowledge the likely advent of market-based mechanisms for maritime transport. Talks are also underway regarding an “Ocean Fund”, where at least half of annual EU ETS shipping auction revenues could be directed towards innovation and climate action for the sector.

Issues such as the free allocation of allowances for the sector to protect against leakage and ensure predictability, how to set a baseline from which current shipping emissions would be measured against for allocation purposes, and harmonizing European reforms with the development of international regulations are yet to be fully charted. However, when it comes to curbing emissions from the maritime transport sector, the EU is steaming ahead.

As ambitious as all of these plans (and the dozens of others unmentioned here) are, the EU, as a consensus-based family of nations, cannot carry them out without making them attractive, or at least acceptable, to its members. The diversity of the Member States and their economies often makes this a challenge, with some countries arguing for increased ambition, while lower-income and fossil fuel-dependent states are more reluctant. When the climate neutrality target was first agreed upon by government leaders in December 2019, for example, Poland was the only state not to sign on, citing the need for more economic transition provisions before committing to increased ambition.

The European Commission will have to dedicate ample time and other resources to addressing these worries. And it has been paying attention to this need, most notably leading to the launch of the 17.5 billion euro Just Transition Fund. Carbon pricing developments may well be hampered by these concerns – but putting a price on emissions could also do its fair share in countering them. As of Phase IV of the EU ETS, the European Commission has introduced the Modernization Fund. This fund exists specifically for the benefit of ten lower-income Member States, who can draw from it for investments in renewable energy, energy efficiency, energy storage, energy networks, and just transition projects. The fund will be made up of the revenues from the auctioning of two percent of total allowances available in Phase IV. The total size of the fund will depend on the carbon price over time but is estimated to reach some 14 billion euros over the coming decade. This is in addition to the Innovation Fund, the successor of the NER300 programme, which will be funded through the sale of 450 million allowances between 2020-2030 and is to be spent on the development of innovative low-carbon technologies across all Member States.

As the many pieces of the European Green Deal take shape and fall into place, they will continue to undulate and influence both each other and the trajectories of broader European and global climate policy. Ensuring a clear and stable price on carbon will remain one of the pillars of the policy package and is an essential driver for long-term decarbonization on the road to net-zero emissions, both on the continent and beyond. In this regard, the coming months will be pivotal in how Europe’s carbon pricing instruments unfold. How they can dance with other regions’ climate policies on the world stage—without jeopardizing their ultimate goal of a just transition to the world’s first climate-neutral continent—has captured the attention of anyone with an active interest in securing the future of this planet. Now, all eyes are on June.

Co-authors: Jana Elbrecht and Maia Hall